My Trip To Germany, After Many Doubts

Many times my

friends invited me to visit them at their home in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, and my

relatives called me to come to Dusseldorf. But because I was firm in

my rejection of anything German, based on studies of the Holocaust in Chislavichi and Monastyrshchina

where my father and mother ZA"L had been born and many family members

slaughtered, I could not allow to myself to accept their invitations. But time

passes, wounds are healed and pain subsides. And two important events which

happened recently made me change my mind. The first event was Simon Wiesenthal's

announcement that he ended his uncompromising hunt after Nazi criminals because

there was all but none of them left. The second one was the book by Y. Tsinman "Babyi Yary Smolenshchiny" and my phone

talks with its author from which I understood better who were the true butchers

in that region. So, I made a very good and interesting trip. The scenery of

Bavarian Alps was simply breathtaking. But I'll limit

myself with telling only about the places interesting from the point of view of

our history, Jewish in general and Horowitz in particular. The first of them was the city of

Frankfurt, the second one

–Cologne.

Frankfurt-Am-Main

Just

unexpectedly, the embankment of Main river in Frankfurt

reminded me of the place where I had spent my young years, then this town

was called Kalinin, now it is Tver. The width of Main and the rate

of its flow were the same as of Volga in its beginning,

and Alte Brukke bridge over Main bas the copy of Old Bridge in Tver which had been constructed at the time of Czars.

I came to the

embankment after I visited the Jewish Museum of Frankfurt, which exposition

uncovers the history of the city's Jewish community, from the Middle Ages till the Holocaust. In this history our great

family was honorably represented by rabbis Pinchas

Horowitz and his son Zvi Hirsh, and also by rabbi,

writer and scholar Dr. Marcus Horowitz.

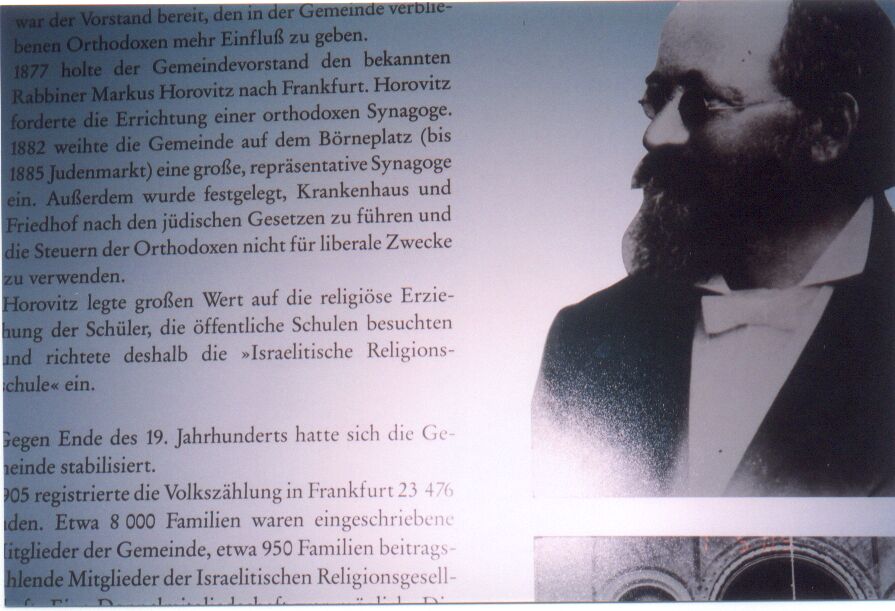

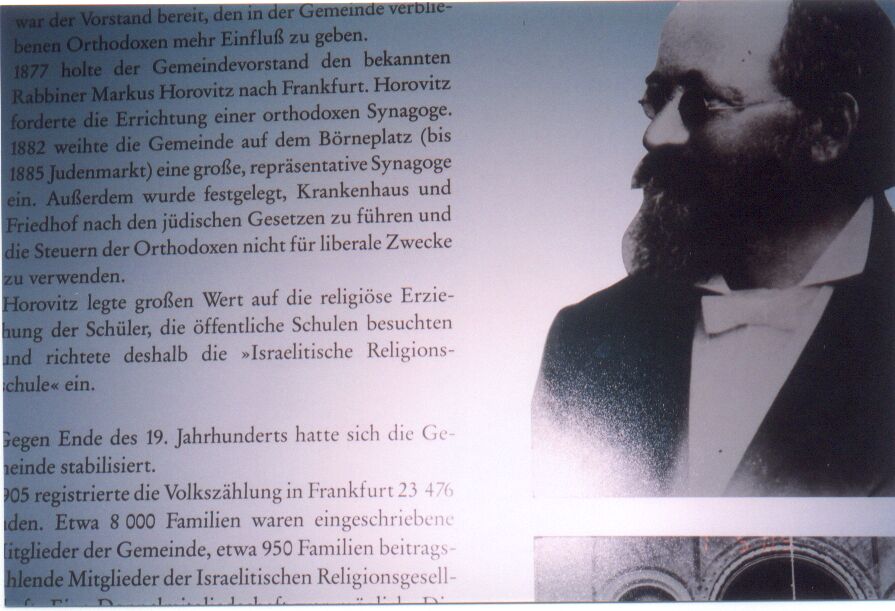

Rabbi Dr. Marcus Horowitz

After a short

break on the bench in the shade of tall trees, I directed my steps to the

Judengasse

Museum, which was situated not far

from the river. In this museum the history of Frankfurt

Jewish community is represented it its visual incarnation: a visitor walks

between the walls of the basements of the houses of the Jewish Ghetto which was

long ago erased from the earth. An old mikveh survived

– it seemed that if filled with water, it would be

ready for use.

Evidence of a Jewish community in

Frankfurt dates back to the 12th

century. At that time, a small group

of Jewish merchants from Worms settled in the town, and quickly flourished and

grew wealthy. Jews had been in Frankfurt prior to this period as well, but never as official

residents – Frankfurt had long been a market town, and Jews visited to trade

there as early as the tenth century. The prosperity of the Frankfurt Jews,

however, was short lived. The year 1241 marked the first of what would be many

massacres and expulsions of the small community. In this first attack, which was

sparked by the refusal of a Jew to convert to Christianity, more than

three-quarters of the city's 200 residents were killed. The remainder quickly

fled the city, but returned by about 1270, when Emperor Frederick II, upset at

the loss in tax-revenue from the wealthy Jewish community, ordered strict

penalties against anyone who attacked Jews. The community once again grew

rapidly, and although forced to pay crippling taxes, was protected against any

physical persecution.

The

outbreak of the Black Plague in 1349, however, changed the Jews' protected

status. Jews were killed and expelled throughout

Germany and Europe,

and Frankfurt was no exception. The community was completely

massacred, and many Jews chose to burn down their own houses while still inside

rather than face death from the angry mob.

Because of

their important economic role, Jews were invited back into

Frankfurt once again in 1360. Their lives in the city however,

were regulated more strictly than ever, culminating in the forcible relocation

of all the Jews of Frankfurt to a ghetto (Juddengasse) in 1462.

Originally containing just 110 inhabitants, the community developed quickly, and

consisted of 3,000 by 1610. Because the area of the ghetto was never expanded,

Jews subdivided their houses and built extra stories to accommodate the

exponential growth. The community soon became a center of Ashkenazi Jewry – the

yeshivas in the city attracted students from all over Europe,

and the community grew very wealthy. In 1616, another pogrom came through the

community. Indeed, affluence was a necessity, for the only way the Jewish

community continued to exist in the fifteenth through seventeenth centuries was

by paying enormous tributes in exchange for protection.

In 1624,

the two centuries of peace came to a crashing halt as the ghetto was raided and

plundered by a mob of artisans and petty merchants, led by Vincent Fettmilch. The group was unhappy with the prominent position

of the Jews, and many also owed money to the Jewish moneylenders. Unlike the

previous expulsions, however, this one ended happily for the Jewish residents of

Frankfurt. The emperor outlawed the rioters, put their leaders to

death, and ceremoniously returned the Jew to the ghetto on the twentieth day of

the month of Adar, which has been celebrated in Frankfurt ever since as "Purim Winz"

("the Purim of Vincent").

In 1711,

the ghetto burned to the ground after an accidental fire spread out of control,

but the homes and businesses were quickly rebuilt, and the Jews returned to

their isolation. The traditional unity of the Jewish population, however, soon

began to decline, as controversy over the Enlightenment spread throughout

Europe. The rich families that had long controlled the

community saw their influence begin to decline; these families, identifiable by

the crests hanging outside their homes, lost their influence to the maskilim, who advocated secular education and

emancipation. The only exception was the Red Shield, or Rothschild family, which

maintained its importance, and became even more prominent in later

years.

When, in

1806, Frankfurt was incorporated into Napoleon's Confederation of the

Rhine, the Jews' lot improved, at least in the eyes of the advocates of

emancipation. The spread of the ideals of the French Revolution led to the

abolition of the ghetto in 1811. Despite setbacks in 1819 due to the "Hep Hep riots," Jews received

rights equal to those of non-Jews in1824. Frankfurt had by now become a center of the Reform movement, the

ascendance of which led to a widening rift between the Orthodox and Reform

communities. The latter was led during much of the nineteenth century by

philosopher Abraham Geiger; the former, which accounted for only ten percent of

Frankfurt's Jewish population in 1842, was revived by Rabbi Samson Raphael

Hirsch, who founded the Orthodox "Israelitische Religionsgesellschaft" ("Israelite Church Society") in

1851. The community continued to grow and become wealthy; members of the

Rothschild family in particular became known for their philanthropy. Several

orthodox yeshivas were established, as was a Reform Institute for Jewish

Studies, which featured lectures by the scholar Martin Buber.

By the

1900s, Jews in Frankfurt were extremely prosperous and influential. They became

active both in business and politics. Many of the Jews fought for

Germany in World War I.

Frankfurt and the Holocaust

In 1933, a

boycott was targeted at the Jews, and in the subsequent years, more and more

restrictions were placed on the Jewish community. On November 10,

1938, the biggest Orthodox and

Reform synagogues were burned to the ground. Many Jews emigrated from

Frankfurt, and most of those who did not were sent to the

Lodz ghetto, and eventually to the

Dachau and Buchenwald concentration camps. In 1933, 30,000 Jews lived in

Frankfurt; in 1945, only 602 remained.

After the

war, a new community was established, consisting of Holocaust survivors and

displaced persons. In 1989, immigrants from the recently disbanded

Soviet

Union increased the size of the

community to about 7,000. Today, most of the Jews live in the

West End, and are self-employed, particularly as shop-keepers

and real-estate brokers. Anti-Semitism is negligible; instead, assimilation is

the community's dominant social problem. All the city's synagogues, only one of

which dates to before 1938, are Orthodox.

There are

few remnants of Frankfurt's Jewish community left today. The ghetto has been gone

for more than a century, but the spot on which it stood is still accessible. Not

far from the Zeil – the pedestrian mall running

through the city's center – on Bornestrasse, is the

stretch of land on which the Frankfurt Jews lived for more than 400 years. The

Bornestrasse synagogue and the Rothschild home were

both destroyed, but plaques mark the spots where they

stood.

The Westend synagogue, on

Freiherr-vom-Stein-Strasse, is the only Jewish

building in the city with a history. The large grey building was built early in

the 1900s, and was the only synagogue to survive Kristallnacht. The main

sanctuary features vaulting stone arches, a massive cupola and blue-and-white

Star-of-David stained-glass windows. Though a Liberal synagogue before the World

War II, it -like all Frankfurt synagogues

today has separate sections for men and women.

Near the synagogue is Frankfurt's Jewish

community center, opened in

1986, a huge building adorned with large

iron menorahs and stone tablets. The building features concerts,

lectures, a

youth center and the offices of the community administration and

Rabbinate.

The Jewish

museum on Untermainkai is located in a house that once

belonged to the Rothschild family, and features high-tech resources as well as

priceless artifacts, including Moritz Oppenheimer's famous portrait of Mendelsohn and Lessing. But the

most famous part of the museum is the scale-model of the Frankfurt Juddengasse,

reconstructed using the blueprints made in 1711 after it was destroyed by fire.

The intricate model includes 194 buildings. Abutting the MUSEUM JUDENGASSE AM

BÖRNEPLATZ is Frankfurt's OLDEST JEWISH CEMETERY, most of whose

tombstones were vandalized during World War II.

A painstaking restoration project seeks to

register and match the broken stones. The cemetery is surrounded by a high stone

wall into which some 11,000 plaques have been inserted…each details the name,birth-date and place of death of the 11,000 Frankfurt

Jews murdered in the

Holocaust, and creates a starkly moving

testament to the destroyed community. To the rear of the cemetery a checkered

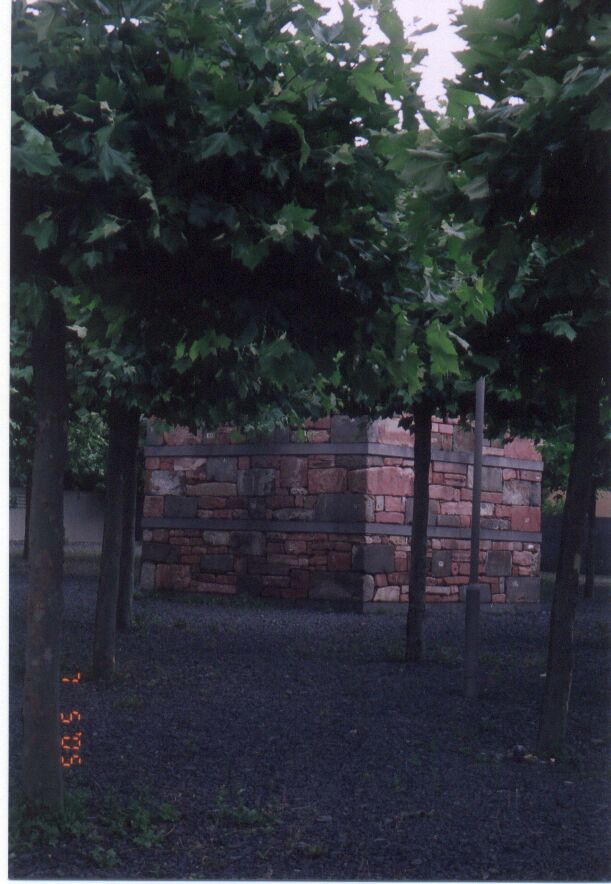

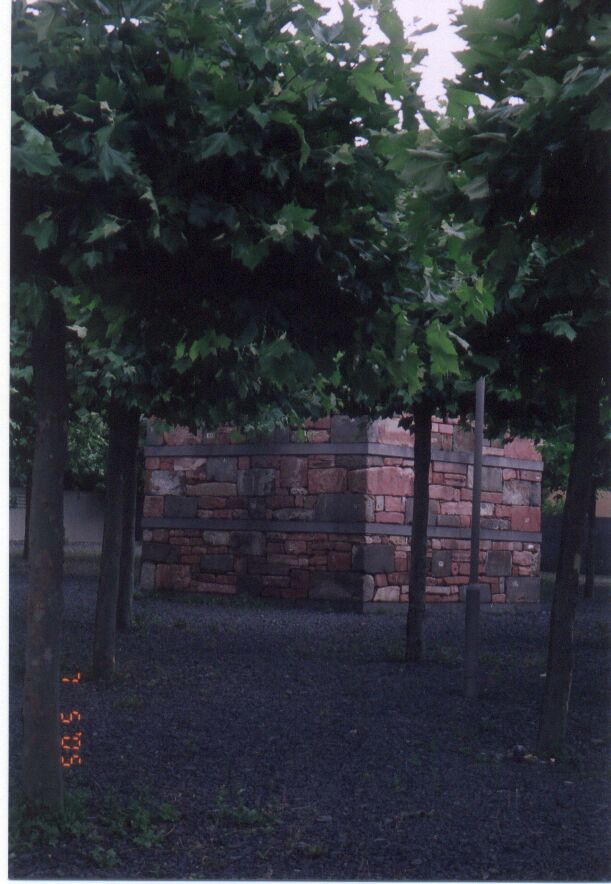

arrangement of trees is the MEMORIAL TO THE BÖRNEPLATZ SYNAGOGUE,

destroyed on Kristallnacht.

Just opposite

the Römer, Frankfurt's l5th-century

city hall, is a HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL, adjacent to

the Paulskirche church where, in 1848, the Frankfurt

National Assembly made an abortive attempt to unify

Germany and to

guarantee human rights and emancipation. (The cited historical

information was found at http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/).

Very close to the

museum is the Old Jewish cemetery, the most of its tombstones were destroyed by

the Nazis in their crazy war against the Jews, live and dead. The fragments of

the tombstones are

laid in small piles and one big pile, the evidences of the 20th century barbarity.

The big part of the survived tombstones are situated

along the cemetery's wall or in the group at its far part, opposite from the

gate. A small number of

tombstones are organized into a special group – these are the matzevot of prominent residents of

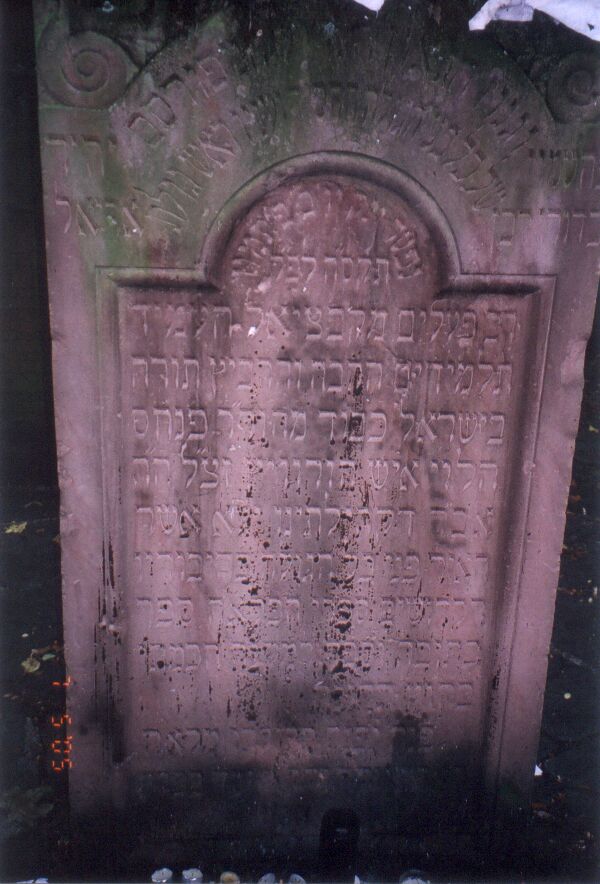

Frankfurt. Matzeva of R., the

author of "Pnei Yehoshua" is

there as well as he tombstones of the Rotschild Family members. Here are also the tombstones of R.

Pinchas and his son R. Zvi

Hirsh, for them I actually came to Frankfurt.

The

Old Jewish Cemetery in Frankfurt

Slowly I was

coming to the dear graves. There were many candles, notes, just like at the

Western Wall in Jerusalem. The

inscriptions on the tombstones were partly faded, but nevertheless I managed to

read the words of sorrow and gratitude of the Jews whom they taught and led.

Rabbi Pinchas Horowitz

Rabbi Zvi Hisrsh

Horowitz

The hands of my watch were

unmercifully moving ahead, the museum's closing hour was getting nearer and

nearer. Trembling, I locked the

heavy iron gate and gave the last glance to the Cube, tolling between young

maple trees, assembled with the fragments of the ruined

synagogue, and turned to the train station.

Frankfurt: in the memory of Judengasse

Cologne

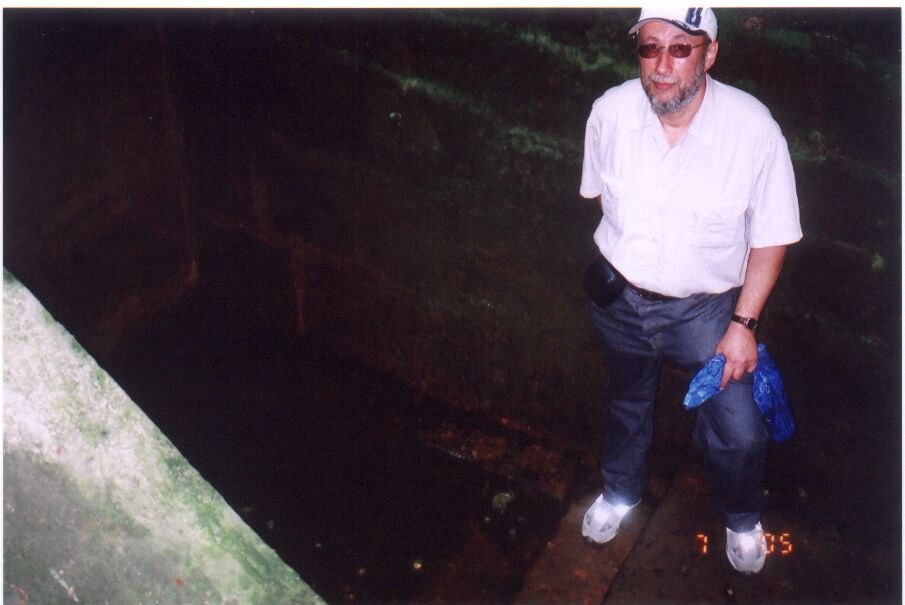

The Mikveh site in

Cologne is frequented by numerous

groups of tourists from all over the world: Germans, Americans, omnipresent

Japans, etc. Sticking to the transparent roof, they peep intently at the

stairway of the medieval mikva descending deep into

the dark. According to the historians, it was constructed as early as in 12th

century.

COLOGNE first

became home to Jews who arrived with the Romans, perhaps as early as 7 0.Colonia

Jews are mentioned in two edicts by Byzantine Emperor Constantine in the years

32 1 and 331.By the 11th century, there was a Jewish substantial community.

Cologne has had many

illustrious Jewish citizens, including composer Jacques Offenbach and Zionist

philosopher Moses Hess. In 1904, after the death of Theodor Herzl, the headquarters of

the World Zionist Organization was moved from Vienna to Cologne when the

Cologne Zionist leader, David Wolffsohn, succeeded to

its presidency. The Cologne-based Solomon Oppenheim

Bank is one of the few major businesses in

Germany again under

its pre-war Jewish ownership. The medieval Jewish quarter that existed until

Jews were expelled from Cologne in 1424 was

situated in front of the RATHAUS, the Gothic city hall. The lane that runs in

front of the building is the JUDENGASSE. Near the small space next to the

RA THAUS (near today's flagpoles) stood the medieval main synagogue, women's

synagogue, hospital ,bakery and community center. All

that remains of medieval Cologne Jewry is the MIKVEH, reached by

descending fifty feet down a Romanesque stairwell of hewn sandstone. The pool is

fed by the Rhine and dates from

1170; it was sealed after the l5th-century expulsion and rediscovered only

during rebuilding after the allies' World War II bombing . Renovated and reopened in

1979,it is topped by a glass pyramid,

Cologne's modern opera

house stands on the site of the 19th-century GLOCKENGASSE SYNAGOGUE destroyed on

Kristallnacht. The plaza that fronts the opera house

has been named OFFENBACHPLATZ, for the composer Jacques Offenbach,son of a

Cologne cantor. The

center of contemporary Cologne Jewry --the community now numbers about 5,000

--is the GREAT ROONSTRASSE SYNAGOGUE, the oonly

Cologne synagogue to

survive the Nazis

Getting the key

from the Old Town

hall upon depositing of my passport, me and my

cousin Arkady descended the stairs. The walls covered

with mold were good

evidences of the centuries that passed. The mikveh was filled with water, it seemed to be ready for ritual immersion. The once

built here synagogue was ruined, the Jewish Quarter, Judengasse does not exist, but the mikveh, this material evidence of our residence in this part of Diaspora

is still alive and attracts everybody's attention!

Cologne: the Old Mikveh

An intercity

express was rushing at 250 km/h to

Munich, the last point of my trip.

The car I was sitting in was full of Turks, Asians, Arabs. It was new

Germany,

multinational and open. "But will it be so in the long run", I was asking

myself, "or it will be only a short period of tolerance which in a period

of economical or political strife

will be wiped will a wave of hatred and xenophobia, as it just happened there

many times in the Past?".