On the Fosca, the Calle’s main street, one finds the Bon Astruc da Porta Center. Bon Astruc da Porta had been the head of the Gerona community in the 13th century. It is generally accepted that the great RaMBaN (Nahmanides), who served as a focus of Jewish scholarship in the city during this period, used this name in his contacts with the authorities.

The Center is located in a few buildings which had once belonged to Jews, including the remains of the ancient synagogue. Today it houses an educational and research center, museum and library.

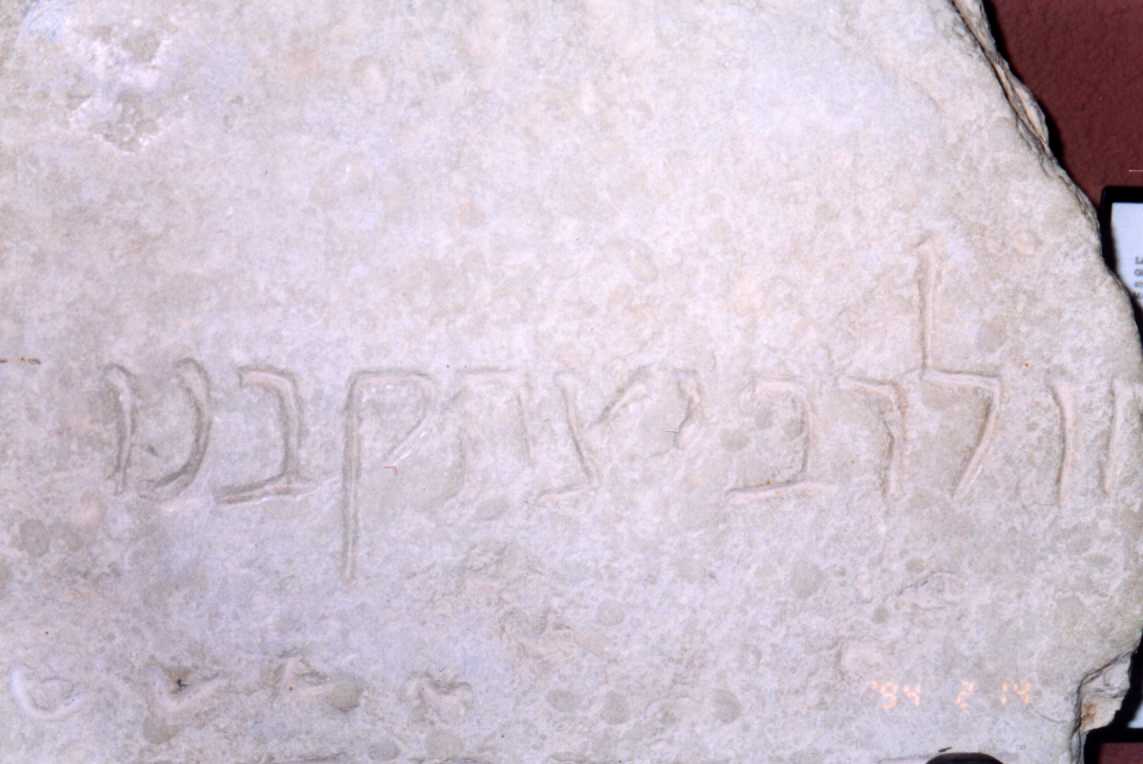

Among the museum’s displays is a stone with an inscription from the old synagogue, as well as a fragment from a tombstone from the destroyed Jewish cemetery located, as in Barcelona, on Montjuic. We can strain our imagination and imagine that the inscription “His son, Rabbi Yitzhak” could well be associated with our Rabbi Yitzhak Ha-Levi and the tombstone itself had once stood on the grave of the father of Rabbi Yitzhak, Rabbi Zerakhyah Ha-Levi.

From Gerona we again continued our way north-east. After crossing the French border, we reached Perpignan, where we spent Shabbat. Perpignan had a sizable Jewish community in the Middle Ages. There are about 100 Jews today in the city, for the most part emigrants from Northern Africa (which, by the way, is also true of other French cities), who jealously support the synagogue and cordially receive guests from Israel. And this takes place in an atmosphere of constant threats from our “cousins,” who have already flooded all of Europe.

From Perpignan we make a one-day side-trip to the north into the Pyrenees. We admire that majestic beauty of the snow-capped peaks and enjoy the solitude and the low population density which contrast so starkly with the landscape of Israel.

The next day we are already in Narbonne famous for its “Jewish sages,” who, according to Avraam ibn Daud in his well-known work “Sefer Ha-Kabbala,” enjoyed in the Middle Ages the same esteem in the Jewish world as the leaders of the Babylonian academies. It was here where Ha-RaZaH, studying with the famous RaMBI, Rabbi Moshe ben Yoseph, advanced his knowledge of Torah. No less well known in the Jewish world of the period were other members of the Narbonne community – its head, the famous Rabbi Makhir and his descendants – Rabbi Todros and the scholar Kalonimos; Rabbi Nathan of Babylon, Rabbi Moshe Ha-Darshan, who headed a Talmudic school; chairman of the rabbinical court Rabbi Avraham ben Yitzhak, author of “Sefer Ha-Eshkol”, and others.

Unfortunately, Narbonne retains no traces of a Jewish presence in the Middle Ages. Thus, we had to be satisfied with a general impression of the historic city center and the imprint from a mezuza on the door frame of a house once occupied by Jews. We saw such characteristic imprints along other points of our trip – sad reminders of the history of Jewish wanderings.

From Narbonne we drove to Carcassonne, a fairy tale city which has retained its medieval fortress walls and towers often used as a backdrop for historical films. Although the appearance of Jews in Carcassone dates from the beginning of the Christian era, the earliest documents which mention Jewish life appear only in the 12th century. Jews here enjoyed considerable privileges and even owned vineyards in the city’s environs. Before the 14th century prominent rabbies, scholars and doctors lived here. When the well-known Talmudic commentator, an opponent of our Rabbi Zerakhyah Ha-Levi, author of “Ha-Maor”, Rabbi Avraham ben David from Posquieres (HaRaBaD) was imprisoned by the local lord, Viconte Roger II freed him and provided him the opportunity to live undisturbed in Carcassonne.

From Carcassonne we drove to Monpellier, capital of the Province of Languedoc, where Jews appeared in the second half of the 11th century. They played a major role in the rapid growth and economic development of the city, but they acquired fame through the rabbinical scholars and doctors. The 12-13th centuries saw the flourishing here of an outstanding school compared even with the Jerusalem Sanhedrin. Well-known are the names of Rabbi Shlomo ben Avraam, his student Rabbi David ben Shaul, the already mentioned RaBaD, Rabbi Moshe ben Shlomo ibn Tibbon, and, of course, our ancestors – Rabbi Pinchas He-Levi and his brother Rabbi Aharon ben Yoseph (Ha-RoEH), who arrived during the first half of the 13th century. Great was the contribution of Jews (David Kimkhi, Yakov ben Makhir, Shlomo de Lunel) in founding here a famous school of medicine which served as the forerunner of one of the oldest European universities. 800 years later M. I. Gurevich, an outstanding aircraft designer and talented descendant of Rabbi Pinchas, would study at this university. From among the material artefacts of a Jewish presence in Montpellier in the Middle Ages there remains a 13-14th century mikvah. We descend the steep steps – the mikvah is full of clean, crystal clear water, ready to perform its original function. A small apartment in the attached building houses a center with an impressive name: The RaMBaM European Mediterranean University Institute. The center manned by a small number of enthusiasts engages in research into the history of the Jewish community of Provence, holds lectures and seminars on Jewish subjects, etc.

The last place on our itinerary is Lunel, located about 20 kilometers to the north-east from Montpellier. It is no easy task to recognize in this out-of-the-way town the majestic “Lunar City” known for its rabbis and religious teachers and one of the great medieval centers of Jewish learning. The local yeshivah acquired such fame in the Jewish world in the 13th century that it was known as the “Place of Torah Study” and “Entrance to the Temple.” Among the long line of “Sages of Lunel” of special merit are the head of the yeshivah Rabbi Meshullam ben Jacob, his sons Rabbi Jacob and Rabbi Aharon, RaMBaM’s translator Rabbi Shmuel ibn Tibbon, and, of course, the great RaZaH – Rabbi Zerakhyah Ha-Levi. author of the “Sefer Ha-Maor”. Incidentially, the city name influenced the author to name one portion of this major work “Ha-Maor Ha-Katan” (Small Heavenly Body) based on it.

There remain no traces of the bygone greatness, nor can one hear a Jewish prayer being recited. One will find neither a synagogue, nor a Hebrew sign on a store. Rather, one is likely to hear a muezzin and to see Arabic ornamental script on the signs. An epoch of our history here has drawn to a close.

Our trip also ended here. The highway quickly returned us to Montpellier, and an express train brought me back to Barcelona. A few hours later I stood on our sun-drenched land, trying without success to understand whether this had all been real or merely an enchanting dream.

October 2002